Belgian Ales

Interestingly enough, at this stage of my life, beer is usually my last choice when consuming a beverage with a meal. There was a time, in my culinarily uneducated youth, when American pilsners and lagers were my beer of choice. Don't get your NASCAR hats in a huff, king of beer drinkers, my simple point is this; Though I've lost my taste for most American beer, when I do get that urge for a frosty cold one, it's a hearty ale or stout that tickles my fancy and I will gladly admit that I have fallen in love with Belgian ales.

Interestingly enough, at this stage of my life, beer is usually my last choice when consuming a beverage with a meal. There was a time, in my culinarily uneducated youth, when American pilsners and lagers were my beer of choice. Don't get your NASCAR hats in a huff, king of beer drinkers, my simple point is this; Though I've lost my taste for most American beer, when I do get that urge for a frosty cold one, it's a hearty ale or stout that tickles my fancy and I will gladly admit that I have fallen in love with Belgian ales.

Belgian beer comprises the most diverse national collection of quality beer in the world, and varies from the popular pale lager to lambic beer and Flemish Red. Belgian beer-brewing's origins go back to the Middle Ages.

There are approximately 125 breweries in the country; in Europe, only Germany, France and the United Kingdom are home to more breweries. Belgian breweries produce about 500 standard beers. When special one-off beers are included, the total number of Belgian beers is approximately 8700. Belgians drink 24 gallons (93 litres) of beer per year on average.

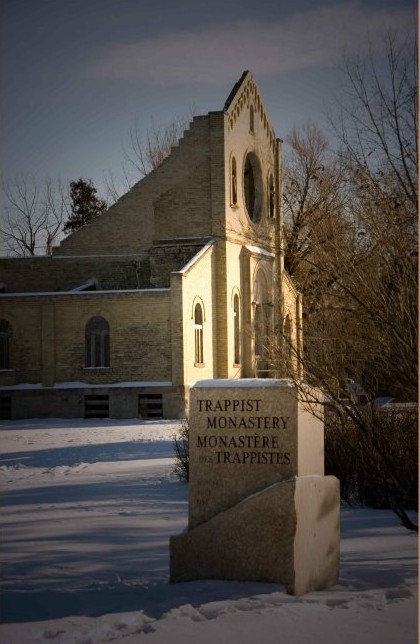

Beer has been made in Belgium since the Middle Ages and it is believed today that beer was brewed at some monasteries during this period, however, no written proof exists. The Trappist monasteries that now brew beer in Belgium, were occupied in the late 18th century primarily by monks fleeing the French Revolution. The first recorded sale of beer (a brown beer) was on June 1, 1861.

The vast majority of Belgian beers are sold only in bottles. Draught beers tend mostly to be pale lagers, wheat beers, regional favorites such as Kriek in Brussels or De Koninck in Antwerp; and the occasional one-off. Customers who purchase a bottled beer (often called a "special" beer) can expect the beers to be served with some pomp and circumstance, most often they are accompanied by a free snack. These days, Belgian beers are sold in brown, or sometimes dark green tinted glass bottles. This avoids any negative effects of light on the beverage. They are usually sealed with a cork, a metal crown cap, or sometimes both. Some beers are bottle conditioned, which means they are reseeded with yeast, in order for an additional fermentation to take place.

The vast majority of Belgian beers are sold only in bottles. Draught beers tend mostly to be pale lagers, wheat beers, regional favorites such as Kriek in Brussels or De Koninck in Antwerp; and the occasional one-off. Customers who purchase a bottled beer (often called a "special" beer) can expect the beers to be served with some pomp and circumstance, most often they are accompanied by a free snack. These days, Belgian beers are sold in brown, or sometimes dark green tinted glass bottles. This avoids any negative effects of light on the beverage. They are usually sealed with a cork, a metal crown cap, or sometimes both. Some beers are bottle conditioned, which means they are reseeded with yeast, in order for an additional fermentation to take place.

Trappist Beers

This term is properly applied only to a brewery in a monastery of the Trappists, one of the most severe orders of monks. This order, established at La Trappe, in Normandy, is a stricter observance of the Cistercian rule (from C'teaux, in Burgundy), itself a breakaway from the Benedictines. Among the dozen or so surviving abbey breweries in Europe, seven are Trappist, six being located in Belgium and they were all established in their present form by Trappists who left France after the turbulence of the Napoleonic period. The Trappists have the only monastic breweries in Belgium, all making strong ales, with a refermentation in the bottle. Some gain a distinctly rummy character from the use of candy-sugar in the brew-kettles. They do not represent a style, but rather are very much a family of beers. The three abbeys in the French-speaking part of the country, are all in the forest country of the Ardennes, where hermitages burned charcoal to fuel early craft industries. It is not usually possible to visit the abbeys without prior arrangement by letter, and can be difficult even then. Most offer their beers in a café or auberge/inn located nearby the actual monastery brewery.

In 1997, eight Trappist abbeys founded the International Trappist Association (ITA) to prevent non-Trappist, commercial companies from abusing the Trappist name. This private association created a logo that is assigned to goods (cheese, beer, wine, etc.) that respect precise Trappist production criteria. For the beers, these criteria are the following:

In 1997, eight Trappist abbeys founded the International Trappist Association (ITA) to prevent non-Trappist, commercial companies from abusing the Trappist name. This private association created a logo that is assigned to goods (cheese, beer, wine, etc.) that respect precise Trappist production criteria. For the beers, these criteria are the following:

~The beer must be brewed within the walls of a Trappist abbey, by or under control of Trappist monks.

~The brewery, the choices of brewing, and the commercial orientations must depend on the monastic community.

~The economic purpose of the brewery must be directed toward assistance and not toward financial profit.

This association has a legal standing, and its logo gives to the consumer some information and guarantees about the produce. There are currently seven breweries that are allowed to have their products wear the Authentic Trappist Product logo.

Abbey Beers

(Bières d’Abbaye or Abdijbier) are brewed by commercial brewers, and license their name from abbeys, some defunct, some still operating. Abbey beers mainly came into being following World War II when Trappist beers experienced a new popularity. The Abbey beers were developed to take advantage of the public's interest in the Trappist beers. This is why the single key component of an Abbey beer is its name: there is always the name of a monastery (either real or fictitious). Like the Trappist beers, Abbey beers do not connote a beer style, but rather a marketing term; however, since the purpose of Abbey beers is to imitate the Trappists, like the Trappists, most of their beers are either a dubbel or tripel.

The Brewing Monks

Monastic beers, as explained in our previous chapter are generally defined as beers referring to monks or to religious symbols. When they wear the name of an abbey, they are then called abbey beers.

The Belgian monastic beers that we know today belong to a family of beers that appeared during the first quarter of the 20th century. Truly authentic monastic beers were created centuries ago, and some famous examples remain today, such as Mallersdorf and Andechs of Germany. Unfortunately, the number of authentic monastic breweries is rather limited today and the vast majority of the monastic/abbey beers that are available today have little or no direct links with monks or nuns.

However, these abbey beers use the high secular reputation of genuine monastic beers to promote an image of tradition and quality.

The monks are often represented as jovial characters, very often corpulent, as to show the quality of the beer and its associated welfare. Images and names are carefully chosen to evoke values of tradition and know-how. The brewers, while paying homage to the work that was formerly carried out by the monks, try to suggest that their beer is the vehicle of these secular values of quality.

Very often, these monastic beers see great success, sometimes becoming more famous than genuine monastic or Trappist beers they imitate. The fact that they are generally not brewed by the monks does not predict their quality. Some of them are indeed excellent beers .

Types of Belgian Beer

Abbey Ales (Dubbel, Tripel, Singel).

Monastic or abbey ales are an ancient tradition in Belgium in much the same manner as wine production was once closely associated with monastic life in ancient France. Currently, very few working monasteries brew beer within the order, but many have licensed the production of beers bearing their abbey name to large commercial brewers. These "abbey ales" can vary enormously in specific character, but most are quite strong in alcoholic content, generally ranging from between 6- 10 % alcohol by volume. Generally, abbey ales are labeled as either Dubbel or Tripel, though this is not a convention that is slavishly adhered to. The former conventionally denotes a relatively less alcoholic and often darker beer, while the latter can often be lighter or blond in color and have a syrupy, alcoholic mouthfeel that invites sipping, as opposed to rapid drinking. The lowest gravity abbey ale in a Belgian brewer’s range will conventionally be referred to as a Singel, though it is rarely labeled as such.

Altbier

Put simply, an Altbier has the smoothness of a classic lager with the flavors of an ale. A more rigorous definition must take account of history. Ale brewing in Germany predates the now predominant lager production. As the lager process spread from Bohemia, some brewers retained the top fermenting ale process, but also adopted the cold maturation associated with lager. Hence the name ’Old Beer’ (Alt means old in German). Altbier is associated with Dusseldorf, Munster, and Hanover. This style of ale is light to medium-bodied, less fruity, less yeasty, and has lower acidity than a traditional English ale. In the US, some amber ales are actually in the alt style.

Belgian Style Golden Ale

Belgian golden ales are pale to golden in color with a lightish body for their deceptive alcoholic punch, sometimes having as much as 9% alcohol by volume. The benchmark example, Duvel (Devil) from Belgium, is quite heavily hopped, to give a floral nose and a tangy, fruity finish. Typically such brews undergo three fermentations, the final one being in the bottle, resulting in fine champagne-like carbonation, and a huge rocky white head when they are poured. Often such beers can be cellared for six months to a year to gain roundness. These beers are probably best served chilled to minimize the alcoholic mouthfeel.

Belgian Style Strong Ale

Beers listed in this category will generally pack a considerable alcohol punch and should be approached much like one would a Barley Wine. Indeed, some of them could be considered Belgian style barley wines, such as those beers from Brasserie Dubuisson. Expect a fruity Belgian yeast character and a degree of sweetness, coupled with a viscous mouthfeel.

Belgian Style Red Ale

These are also known as ’soured beers’ and their defining character classically comes from having been aged for some years in well-used large wooden tuns, to allow bacterial action in the beer and which imparts a sharp, sour character. Hops do not play much role in the flavor profile of these beers, but whole cherries can be macerated with the young beer to produce a cherry flavored Belgian Red Ale. These styles are almost exclusively linked to one producer in northern Belgium, Rodenbach. These ales are among the most distinctive and refreshing to be found anywhere.

Belgian Style Amber Ale

This is a not a classic style beer, but nonetheless encapsulates various beers of a similar Belgian theme that do not fit into the more classic mold. Expect amber hued, fruity and moderately strong ales (6%ABV) with a yeasty character. Typical examples of the style would be Flemish beers such as De Koninck and Straffe Hendrik.

Belgian Style Blonde Ale

This is not a classic style of Belgian ale, but covers the more commercially minded Belgian ales that are lighter in color and moderate in body and alcoholic strength. Fruity Belgian yeast character and mild hop flavor should be expected.

Biere de Garde

Biere de Garde is a Flemish and northern French specialty ale generally packaged distinctively in 750ml bottles with a cork. Historically, the style was brewed as a farmhouse specialty in February and March, to be consumed in the summer months when the warmer weather didn’t permit brewing. Typically produced with a malt accent, this is a strong (often over 6%), yet delicate, bottle conditioned beer. These brews tend to be profoundly aromatic and are an excellent companion to hearty foods.

Flemish Style Brown Ale

These are complex dark beers most closely associated with the town of Oudenaarde in Flanders. The authentic examples are medium to full bodied beers that are influenced by a number of factors: high bicarbonate in the brewing water to give a frothy texture; a complex mix of yeasts and malts; blending of aged beers; and aging in bottle before release. In the best examples, the flavor profile is reminiscent of olives, raisins, and brown spices and could be described as ’sweet and sour.’ These beers are not hop-accented and are of low bitterness.

Kolsch

Kolsch is an ale style emanating from Cologne in Germany. In Germany (and the European Community) the term is strictly legally limited to the beers from within the city environs of Cologne. Simply put Kolsch has the color of a pilsner with some of the fruity character of an ale. This is achieved with the use of top fermenting yeasts and pale pilsner malts. The hops are accented on the finish, which classically is dry and herbal. It is a medium to light bodied beer and delicate in style. Most examples one will encounter in the US are brewpub draft interpretations produced during the summer months, though some commercial brewers produce a summer ale in the kolsch style.

Saison

Saison beers are distinctive specialty beers from the Belgian province of Hainuat. These beers were originally brewed in the early spring for summer consumption, though contemporary Belgian saisons are brewed all year round with pale malts and well dosed with English and Belgian hop varieties. Lively carbonation ensues from a secondary fermentation in the bottle. The color is classically golden orange and the flavors are refreshing with citrus and fruity hop notes. Sadly, these beers are under appreciated in their home country and their production is limited to a small number of artisanal producers who keep this style alive.

Trappist Ale

According to EC law, trappist ale may only come from six abbeys of the trappist order that still brew beer on their premises. Five are in Belgium and one, La Trappe comes from Holland. Although the styles may differ widely between them, they all share a common trait of being top fermented, strong, bottle conditioned, complex, and fully flavored brews. At most, each abbey produces three different varieties of increasing gravity. These can often improve with some years of cellaring. In all there are 15 different trappist beers from the six monasteries. Trappist ales are among the most complex and old fashioned of beers that one can find--little wonder that many connoisseurs treat them as the holy grail of beer drinking.

The Trappist order originated in the Cistercian monastery of La Trappe, France. Various Cistercian congregations existed for many years, and by 1664 the Abbot of La Trappe felt that the Cistercians were becoming too liberal. He introduced strict new rules in the abbey and the Strict Observance was born. Since this time, many of the rules have been relaxed. However, a fundamental tenet, that monasteries should be self-supporting, is still maintained by these groups.

Monastery brewhouses, from different religious orders, existed all over Europe, since the middle-ages. From the very beginning, beer was brewed in French cistercian monasteries following the Strict Observance. For example, the monastery of La Trappe in Soligny, already had its own brewery in 1685. Breweries were only later introduced in monasteries of other countries, following the extension of the trappist order from France to the rest of Europe. The Trappists, like many other religious people, originally brewed beer to feed the community, in a perspective of self-sufficiency. Nowadays, trappist breweries also brew beer to fund their works, and for good causes. Many of the trappist monasteries and breweries were destroyed during the French Revolution and the World Wars. Among the monastic breweries, the Trappists were certainly the most active brewers: in the last 300 years, there were at least eight Trappist breweries in France, six in Belgium, two in the Netherlands, one in Germany, one in Austria, one in Bosnia and possibly other countries. Today, six trappist breweries remain active, in Belgium.

Monastery brewhouses, from different religious orders, existed all over Europe, since the middle-ages. From the very beginning, beer was brewed in French cistercian monasteries following the Strict Observance. For example, the monastery of La Trappe in Soligny, already had its own brewery in 1685. Breweries were only later introduced in monasteries of other countries, following the extension of the trappist order from France to the rest of Europe. The Trappists, like many other religious people, originally brewed beer to feed the community, in a perspective of self-sufficiency. Nowadays, trappist breweries also brew beer to fund their works, and for good causes. Many of the trappist monasteries and breweries were destroyed during the French Revolution and the World Wars. Among the monastic breweries, the Trappists were certainly the most active brewers: in the last 300 years, there were at least eight Trappist breweries in France, six in Belgium, two in the Netherlands, one in Germany, one in Austria, one in Bosnia and possibly other countries. Today, six trappist breweries remain active, in Belgium.

The Breweries

Brasserie d'Orval ![]() Founded: 1931

Founded: 1931

The most singular of the Trappist brewing abbeys, in both its architecture and its beer. The name derives from Vallée d'Or ("Golden Valley"). Legend has it that Countess Matilda of Tuscany (c1046-1115) lost a gold ring in the lake. When it was brought to the surface by a trout, she thanked God by endowing a monastery. The monastery, originally Benedictine, later Cistercian, was certainly brewng before the French Revolution. It was sacked at that time, then rebuilt between 1929 and 1936. It is on the French frontier, at Villers-devant-Orval in the Belgian province of Luxembourg, not far from Florenville. The finest craftsmen of the period worked on this particularly abbey, which was seen to crown the centenary of the modern kingdom of Belgium. The present Abbey, officially called Notre Dame d'Orval, stands alongside the ruins of the old. Bread and cheese are made for sale, as well as a startlingly dry, hoppy, ale of approximately 6.2 abv, with an dark orange colour. This world-classic brew gains some of its astonishing complexity from a secondary fermentation with multiple strains of yeast, including "semi-wild" Brettanomyces which imparts a "hop-sack" or "horse-blanket" character. Devotees like to bottle-age this beer for between six months and three years.

The most singular of the Trappist brewing abbeys, in both its architecture and its beer. The name derives from Vallée d'Or ("Golden Valley"). Legend has it that Countess Matilda of Tuscany (c1046-1115) lost a gold ring in the lake. When it was brought to the surface by a trout, she thanked God by endowing a monastery. The monastery, originally Benedictine, later Cistercian, was certainly brewng before the French Revolution. It was sacked at that time, then rebuilt between 1929 and 1936. It is on the French frontier, at Villers-devant-Orval in the Belgian province of Luxembourg, not far from Florenville. The finest craftsmen of the period worked on this particularly abbey, which was seen to crown the centenary of the modern kingdom of Belgium. The present Abbey, officially called Notre Dame d'Orval, stands alongside the ruins of the old. Bread and cheese are made for sale, as well as a startlingly dry, hoppy, ale of approximately 6.2 abv, with an dark orange colour. This world-classic brew gains some of its astonishing complexity from a secondary fermentation with multiple strains of yeast, including "semi-wild" Brettanomyces which imparts a "hop-sack" or "horse-blanket" character. Devotees like to bottle-age this beer for between six months and three years.

Bières de Chimay ![]() Founded: 1863

Founded: 1863

The best-known of the Trappist brewing monaseries. This abbey, also called Notre Dame, stands on a small hill called Scourmont, near the hamlet of Forges, not far from the town of Chimay, also on the French border, but in the province of Hainaut. Originally a glass-smelting town, Chimay is now a center for tourism in the Ardennes. The abbey, in the Romanesque style, was built in 1850. While the early abbeys brewed for their own communities, Chimay was he first to sell its beer commercially. Between the two World Wars, it coined the appellation "Trappist Beer." After World War II, Chimay's great brewer Father Théodore, worked with a famous Belgian brewing scientist Jean De Clerck to isolate the yeasts that identified Chimay's beers as classic Trappist brews. These yeasts, which work at very high temperatures (up to 30C; 86F), impart a character reminiscent of Zinfandel or Port wine, especially to Chimay's 7.0 abv and 9.0 abv beers, which have a color to match. Between the two is a drier, paler, hoppier version at 8.0abv. In ascending order of strength, the standard bottlings are identified by red, white and blue crown tops. There are also larger, corked, bottles as Première, Cinq Cents and Grande Réserve. The strongest will mature in the bottle for at least five years. It makes an excellent accompaniment to Chimay's Trappist cheese (similar to a Port Salut) and is even better with Roquefort.

The best-known of the Trappist brewing monaseries. This abbey, also called Notre Dame, stands on a small hill called Scourmont, near the hamlet of Forges, not far from the town of Chimay, also on the French border, but in the province of Hainaut. Originally a glass-smelting town, Chimay is now a center for tourism in the Ardennes. The abbey, in the Romanesque style, was built in 1850. While the early abbeys brewed for their own communities, Chimay was he first to sell its beer commercially. Between the two World Wars, it coined the appellation "Trappist Beer." After World War II, Chimay's great brewer Father Théodore, worked with a famous Belgian brewing scientist Jean De Clerck to isolate the yeasts that identified Chimay's beers as classic Trappist brews. These yeasts, which work at very high temperatures (up to 30C; 86F), impart a character reminiscent of Zinfandel or Port wine, especially to Chimay's 7.0 abv and 9.0 abv beers, which have a color to match. Between the two is a drier, paler, hoppier version at 8.0abv. In ascending order of strength, the standard bottlings are identified by red, white and blue crown tops. There are also larger, corked, bottles as Première, Cinq Cents and Grande Réserve. The strongest will mature in the bottle for at least five years. It makes an excellent accompaniment to Chimay's Trappist cheese (similar to a Port Salut) and is even better with Roquefort.

Brasserie de Rochefort ![]() Founded: 1595

Founded: 1595

The least well-known of the established Trappist breweries. Notre Dame de St Rémy is near the small town of Rochefort, in the province of Namur, where the valley of the river Meuse rises into the Ardennes. The settlement dates from at least 1230, when it was a convent, and brewed at least as early as 1595. The oldest parts of the buildings date from the 1600s. After the Napoleonic period, the abbey was restored in 1887. The beers, tawny to brown in color, have an earthy honesty, perhaps deriving from a quite simple formulation, in which dark candy sugar is a significant ingredient. They have flavors reminiscent of figs, bananas and chocolate. The range is divided, according to an old Belgian measure of density, into beers of 6.0, 8.0 and 10.0 degrees. These have 7.5, 9.2 and 11.3 per cent alcohol by volume. The brewery has always quietly gone about its business, but in recent years its 10-degree beer has won a growing appreciation. The abbey does not have its own inn, but the beers can be tasted locally at two local hotels: Limbourg (also good for charcuterie and game), and the slightly more expensive, Malle Post.

The least well-known of the established Trappist breweries. Notre Dame de St Rémy is near the small town of Rochefort, in the province of Namur, where the valley of the river Meuse rises into the Ardennes. The settlement dates from at least 1230, when it was a convent, and brewed at least as early as 1595. The oldest parts of the buildings date from the 1600s. After the Napoleonic period, the abbey was restored in 1887. The beers, tawny to brown in color, have an earthy honesty, perhaps deriving from a quite simple formulation, in which dark candy sugar is a significant ingredient. They have flavors reminiscent of figs, bananas and chocolate. The range is divided, according to an old Belgian measure of density, into beers of 6.0, 8.0 and 10.0 degrees. These have 7.5, 9.2 and 11.3 per cent alcohol by volume. The brewery has always quietly gone about its business, but in recent years its 10-degree beer has won a growing appreciation. The abbey does not have its own inn, but the beers can be tasted locally at two local hotels: Limbourg (also good for charcuterie and game), and the slightly more expensive, Malle Post.

Brouwerij Westvleteren ![]() Founded: 1838

Founded: 1838

The smallest of the Trappist breweries, the abbey of St. Sixtus, at West Vleteren, near Ieper and Poperinge, dates from the 1830s. Its beers are not filtered or centrifuged at any stage of production, and emerge with firm, long, big, fresh, malty flavors and suggestions of plum brandy. The Belgian degree system is again used to identify the beers. The figures 4.0, 6.0, 8.0 and 12.0 on the crown cork roughly reflect the alcohol content in this instance, though that cannot be precise in a strong, bottle-coniditioned, ale. The strongest might be closer to 11.5 but has on occasion been rated the most potent beer in Belgium. The beers are available next door at the Café In De Vrede. Otherwise, trade and public alike have to go to a serving hatch at the abbey where a recorded phone message tells callers which beer will be available, and when. If the 12 is on sale, cars will begin lining up long before the 10 AM opening time in the morning. Each car is rationed to ten cases. The monks are inflexible on this point, even toward a café-owner who makes a 1,500-mile round-trip from say Odense, on the Danish island of Fynen. "We make as much beer as we need to support the abbey and no more," say the monks.

The smallest of the Trappist breweries, the abbey of St. Sixtus, at West Vleteren, near Ieper and Poperinge, dates from the 1830s. Its beers are not filtered or centrifuged at any stage of production, and emerge with firm, long, big, fresh, malty flavors and suggestions of plum brandy. The Belgian degree system is again used to identify the beers. The figures 4.0, 6.0, 8.0 and 12.0 on the crown cork roughly reflect the alcohol content in this instance, though that cannot be precise in a strong, bottle-coniditioned, ale. The strongest might be closer to 11.5 but has on occasion been rated the most potent beer in Belgium. The beers are available next door at the Café In De Vrede. Otherwise, trade and public alike have to go to a serving hatch at the abbey where a recorded phone message tells callers which beer will be available, and when. If the 12 is on sale, cars will begin lining up long before the 10 AM opening time in the morning. Each car is rationed to ten cases. The monks are inflexible on this point, even toward a café-owner who makes a 1,500-mile round-trip from say Odense, on the Danish island of Fynen. "We make as much beer as we need to support the abbey and no more," say the monks.

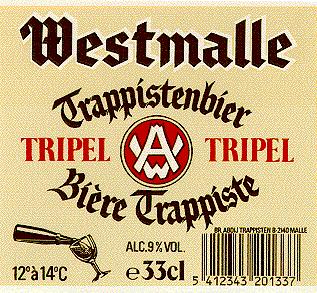

Brouwerij Westmalle ![]() Founded: 1836

Founded: 1836

Famous for one beer in particular, a world classic, though its makes three. The abbey of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart is in flat countryside at West Malle, between the city of Antwerp and the Dutch border. The monastery was established in 1794, and has brewed since 1836. It is thus the oldest of Belgium's post-Napoleonic Trappist breweries. Its renown, though, derives from the introduction of golden Trappist ales to meet competition from fashionable Pilsners after World War II. Its beers include a marvellously subtle, golden "Single" (curiously called Extra), brewed at 4.0 per cent for the monks' own consumption, but sometimes also found outside the abbey; a dark-brown, fruity Dubbel, at 6.5; and its most famous beer, its golden-to-bronze, aromatic, orangey-tasting, complex Tripel, at 9.0. These Trappist classics have popularised the notion that an "abbey-style Double" should be strong and dark and a "Triple," yet more potent, but pale. The beers are available in the village at the café Trappisten.

Famous for one beer in particular, a world classic, though its makes three. The abbey of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart is in flat countryside at West Malle, between the city of Antwerp and the Dutch border. The monastery was established in 1794, and has brewed since 1836. It is thus the oldest of Belgium's post-Napoleonic Trappist breweries. Its renown, though, derives from the introduction of golden Trappist ales to meet competition from fashionable Pilsners after World War II. Its beers include a marvellously subtle, golden "Single" (curiously called Extra), brewed at 4.0 per cent for the monks' own consumption, but sometimes also found outside the abbey; a dark-brown, fruity Dubbel, at 6.5; and its most famous beer, its golden-to-bronze, aromatic, orangey-tasting, complex Tripel, at 9.0. These Trappist classics have popularised the notion that an "abbey-style Double" should be strong and dark and a "Triple," yet more potent, but pale. The beers are available in the village at the café Trappisten.

Brouwerij de Achelse Kluis ![]() Founded: 1998

Founded: 1998

Brewing is being revived, on a small scale, at this sixth Trappist abbey, in Belgium, but close to the Dutch city of Eindhoven. The abbey had a brewery before World War II. In 1998, it opened a small pub initially selling Westmalle, prior to making its own beer. This positive step came at a time of less happy news from across the border, where the Koningshoeven abbey was considering consigning its Schaapskooi brewery, producer of the La Trappe ales, to a joint venture with a large, commercial lager-maker.

Brewing is being revived, on a small scale, at this sixth Trappist abbey, in Belgium, but close to the Dutch city of Eindhoven. The abbey had a brewery before World War II. In 1998, it opened a small pub initially selling Westmalle, prior to making its own beer. This positive step came at a time of less happy news from across the border, where the Koningshoeven abbey was considering consigning its Schaapskooi brewery, producer of the La Trappe ales, to a joint venture with a large, commercial lager-maker.

My Belgiun Ale of Note

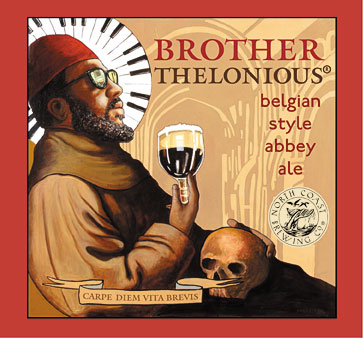

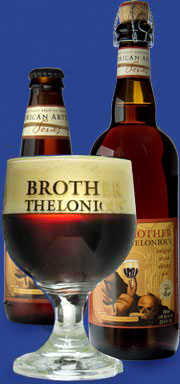

Brother Thelonious

Brother Thelonious

Belgian Style Abbey Ale

Not only have I had the pleasure of partaking of this abbey ale, it holds a special place in my heart  because of its roots to the father of Jazz, Thelonius Monk.

because of its roots to the father of Jazz, Thelonius Monk.

Like a Belgian “Dark Strong Ale”, the beer is rich and robust with an ABV of 9.3%. The package is a 750 ml bottle with a traditional cork and wire finish or 12oz 4 packs and features a label picturing the jazz master himself.

Style: Belgian Style Strong Dark

Color: Dark mahogany

ABV: 9.4%

Bitterness: 32 IBU's

While I am certainly no expert when it comes the subtleties and nuances of beer and ale, my hope is that, this article will start you on your way to experiencing and experimenting with Belgian ales. Beer tastings and pairings are becoming more and more popular, and in summer, these can be a refreshing alternative to the more widley known wine pairings.

Here are a few suggestions, so you can try your own Belgian Ale tasting and pairing.

Brown Beer

This heavily malted beer style features full-bodied notes of caramel and a sour finish. Best food pairing option: Salty and savory foods taste best; desserts and sweet food will distract from the sugary malt of the beer. Try a serving of hearty steak au poivre, or even a nice cheddar burger topped with bacon and mushrooms.

Blonde or Golden Ale

As the name implies, this beer is pale. There is a very slight, almost undetectable note of fruit that is upstaged by the predominant clean flavor of hops and malt. Best food pairing option: Something spicy, tending toward the hot side. This beer is best as a thirst quencher.

Red Ale

Red ale is a sour style beer that acquires a signature strong, complex flavor from a long maturation period in oak. It has a hint of sweetness and mildly discernible tart fruity notes. Best food pairing option: Salty food is the way to go with red beers. Try a robust meat, such as lamb, buffalo, Italian sausage, or a good, sharp cheddar cheese.

As always, when consuming alcoholic beverages, don't overdue it and drink responsibly.

Till next time, cheers!

Lou

Image Sources

www.fitforeurope.com, www.avcbi-businesscenter.com, www.trappistbeer.net, www.justbeer.files.wordpress.com, www.marions-kochbuch.de, www.drinkbrains.blogspot.com