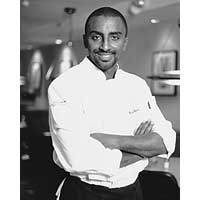

Marcus Samuelsson

Catching up with Chef Marcus Samuelsson, with his hectic and busy schedule, is a very daunting task, so when he agreed to sit with us we were thrilled. We arranged to meet with him at his restaurant, Aquavit on 55th St, NYC. Just back in town from Europe, he is busy taping his show, Inner Chef, along with running his restaurants, Riingo, his new venture C-View in Chicago and of course Aquavit. He was quite gracious and immediately made us feel at ease as we relaxed and talked food with him. He has a perspective on food and cuisine quite like no other chef we have encountered. His descriptives of food in his cookbooks are unparraleled and this soft spoken culinary genius is thinking so outside the box with regard to what he puts on a plate, that he has almost literally created a new box altogether.

Catching up with Chef Marcus Samuelsson, with his hectic and busy schedule, is a very daunting task, so when he agreed to sit with us we were thrilled. We arranged to meet with him at his restaurant, Aquavit on 55th St, NYC. Just back in town from Europe, he is busy taping his show, Inner Chef, along with running his restaurants, Riingo, his new venture C-View in Chicago and of course Aquavit. He was quite gracious and immediately made us feel at ease as we relaxed and talked food with him. He has a perspective on food and cuisine quite like no other chef we have encountered. His descriptives of food in his cookbooks are unparraleled and this soft spoken culinary genius is thinking so outside the box with regard to what he puts on a plate, that he has almost literally created a new box altogether.

His Personal History:

After their birth mother died in a tuberculosis epidemic when he was three years old, Kassahun Tsegie (Marcus' birth name) and his elder sister, Fantaye, were adopted by Ann Marie and Lennart Samuelsson, a homemaker and a geologist, who lived in Goteborg, Sweden. The siblings' names were changed to Marcus and Linda Samuelsson. They also have a biracial adopted sister, Anna Samuelsson. Samuelsson's biological father, Tsegie, is a priest and father of eight of the chef's half-siblings; he still lives in the village where Samuelsson was born. After becoming interested in cooking because of his maternal grandmother in Sweden, Samuelsson studied at the Culinary Institute in Goteborg, where he grew up then apprenticed in Switzerland and Austria.

After their birth mother died in a tuberculosis epidemic when he was three years old, Kassahun Tsegie (Marcus' birth name) and his elder sister, Fantaye, were adopted by Ann Marie and Lennart Samuelsson, a homemaker and a geologist, who lived in Goteborg, Sweden. The siblings' names were changed to Marcus and Linda Samuelsson. They also have a biracial adopted sister, Anna Samuelsson. Samuelsson's biological father, Tsegie, is a priest and father of eight of the chef's half-siblings; he still lives in the village where Samuelsson was born. After becoming interested in cooking because of his maternal grandmother in Sweden, Samuelsson studied at the Culinary Institute in Goteborg, where he grew up then apprenticed in Switzerland and Austria.

Elaine: I really want to talk to you about cuisine. I know that a lot of people are talking about your history and if you would like to talk about that fine, but I'd like to focus on cuisine with you. So there you are, in culinary school and you get a job as an apprentice at Bell Ave. What do you remember most about that experience? Marcus: I remember, and it’s one of the things that keeps me in the field, I was always very excited to go to work. There was always some older cat that had been somewhere who had traveled in the field and who had a lot of stories, and a lot of knowledge about food. I remember thinking I want to have that knowledge and I wanted to be in these stories. It wasn’t like other jobs where it’s flat. It was never flat in the kitchen and it was also balanced. Something comes in like a piece of fish, comes in and they carry it with respect, and filet it and then it goes through this process where you cook it and it goes out to the customer. I never saw the customer’s end of it at all, but this process was interesting to me and everybody had to go through it and put hard work into it. There was also teamwork involved with it. I didn’t cook, I worked in the butcher’s department, so I cut it, filleted it and would send it to the kitchen. It was exciting. Elaine: You were working in a commercial kitchen. Did you expect what you experienced there? Marcus: Well, coming up all my summer jobs, all my experiences, had been either with my grandmother or working in local restaurants or local bakeries. I knew and understood the process; the customer comes in and orders what they like, then we prepare it and send it back out to the customer. I got that. But, I didn’t know the level of detail that was put in to it. I didn’t know that salmon could be prepared 50 different ways. I thought it was grilled salmon or the pouched salmon. You know I didn’t know things like tar –tar or any of that language. Elaine: You went from Bell Ave. into a high luxury environment in a hotel in Switzerland. Other than the luxury food that your exposed to in that atmosphere, what was the difference between the two? Marcus: Well, there was a much higher level of professionalism, there was much more at stake. In Sweden, everyone was nice and you were reprimanded if you did something wrong. In Switzerland you got fired, you disappeared. Guys were gone, they didn’t come back. Lou: Wow, that’s a high standard. Marcus: It is a very high standard, but my chef had a kitchen with sixty guys and only twelve of them were sous chefs. He basically had forty-eight kids running around, mostly from nineteen to twenty four, twenty-five, twenty-six maybe, so he had to be like a tough coach. But he made it very simple. Either you followed the rules or you didn’t. Elaine: No gray area. Marcus: Nothing. There was a line up everyday, everyday! It could be that you didn’t iron your jacket, or that you didn’t wear the tie. It could be that your shoes weren’t polished. But, he gave you all the information you needed. He was very fair because there wasn’t a moment where he didn’t tell you what he wanted. So you just followed the rules. Especially in cooking, it was a lot about following. But he never made it about more than the issue. I don’t think anybody ever got fired for anything that was unfair, you know… Elaine: because it was put in plain sight… Marcus: ....they were clear, they were very clear. Lou: Do you think if you had trained in a less black and white environment, where there was some gray, that you’d be a different chef? Marcus: I don’t know. I do think that it was good for me at that time. He ultimately told you that if you are passionate and you do the work, this would be a positive experience. If you did follow the rules, which were very simple, then lots of positive things came, you know, a reward for following the rules. I got the chance to go to other parts of Switzerland, I got to travel. He maybe gave you an extra day off or whatever the reward would be. It was a very fair system. Forty-five minutes for every fourteen hour day in the lineup is a very small time to have contact, so like anything you adapt. Elaine: Yes and it is very obvious that you are passionate, not only in what we have read about you, but in what you are cooking. From the recipes I have prepared at home to the design of the food on the plate. You talk about travel now. You were on a cruise ship and were globe trotting, going off to cook everywhere. Is there one moment in during that experience that really stands out in your mind? I know there are many. | Marcus: It was really hard, I don’t think I have ever worked as hard as I did on that ship. Switzerland was hard, but you had a day off. If you did really well, then you could have two days off, there was a break, there was down time. You could relax and shower and you're in Switzerland so you could mountain bike or ski. On the ship, you worked everyday; breakfast, lunch, dinner. Everyday, not only Wednesdays and Sundays. No, everyday. Lou: Sounds like all your days kind of blended into one as if it was one long experience. Marcus: Yes. So, not to have that one day to look forward to was very hard. But again I was a young guy and I could adapt. It’s amazing what you can drill your body to do. Lou: Now talk about the cuisine and culinary aspect of it. Obviously, on a cruise ship, you’re going into every market when you go into port. Here you are, going into all of these different ports around the world. What was that like, to experience the culture of all these different countries? Marcus: It was really cool, but it goes two ways. One part of the cruise ship is extremely organized, because you might not pull into that port. Mother Nature is going to decide whether or not you get to go into that port or not. You have a freezer that is always stocked full, because you might be out for six days when you only planned on two.Then there is the other parts of the trip that are a little more creative if you will. Because you are going to the markets there and seeing the cuisine in different areas. This was exciting for us as young cooks. I had the privilege of experiencing authentic food over that year basically every week. There was Thai, Moroccan, American West Coast, Brazilian. Because we went on two trips that went all over the world, they probably had the biggest impact on me. I really liked how this food thing was not owned by the French or the Italians or a certain nationality. Great food was everywhere, which is very simple to understand now, but back then, I didn’t know Mexico was on the food map. I had never seen a Mexican cookbook. I didn’t know anything about Thai food, you know like curry and that sort of thing… Lou: This opened you up to what you are doing now, which is global cuisine. Marcus: I don’t think you can do global unless you have experienced those things. Like watching and saying. "Oh, so that’s how you make a taco," which is the simplest thing. Just a mother warming up the tortilla and putting just a little bit of onion and not cutting the cilantro but using the whole thing or editing the avocado. It's not guacamole, it's actually just a piece they put in there. You know we always try commercializing or over analyzing foods and ingredients, but it’s like they take some lemon and squeeze it over. If they don’t have lemon, they don’t use anything. Just depends, it's honest truth on the highest level. Elaine: Simple. Marcus: Yes... Elaine: You talk about that a lot, being simple.When you reflect on that, is there anything in particular that you learned on that trip that you employ now?

Marcus: When you create a restaurant it’s a little bit different, because as a guest, part of you wants something authentic, but then part of you wants something totally not authentic. Finding that balance is really what makes a restaurant click. When are we delivering something that is authentic and when are we delivering something that is more theater? The plates that we had in Mexico, I could never bring in here because it wouldn’t work. The plates we use here, we stick to Swedish lines, you know, very elegant. The flavors I can make very authentic. It's finding the balance of what works in a restaurant, whether it’s a ginger beer or straight vodka or smoked salmon that stays very authentic. Other times, it's how you're dressed, your vocabulary, the way you're addressing customers. That’s something you create and that’s something you, as a group discuss. How are we going to do this? How are we going to come across? How are we going to pour the water? What bread do we serve? Those are levels that you decide. It’s a concept you work on all the time. Lou: What came out of that experience is the shaping of how you flavor your dishes and ingredients? Marcus: Like Sweden. When you deal with a minority, which Swedish cuisine is, the customer didn’t go out for this. If you are talking about Indian, French, Italian, Chinese, even Japanese, those are world cuisines that people are familiar with and they know what they should taste like. But there’s no one coming up to you with, "Oh, well this cod roast should taste like this." You know what I mean? There’s was no reference point to Swedish cuisine. It makes it a little bit different when you have a reference point to something, because if you don’t, then you become the reference point. Once you become that, you have to define how you should come across with that. |

The story continues...

The story continues...

In 1991 Marcus traveled to New York City and began an eight-month apprenticeship at Aquavit, the well-known New York City eatery. In business since 1987, the Upper East Side restaurant was considered the top Swedish-cuisine restaurant in North America. Following his brief time at Aquavit, Samuelsson returned to Europe to take a position at the world-renowned and three-star Michelin restaurant, Georges Blanc in Lyon, France. “At Georges Blanc I learned that to be a top chef you have to have a passion for success as well as a passion for food,” Samuelsson says. “It’s not enough to be able to prepare delicious food. You have to be consistent as well, and serve two outstanding meals a day to each and every guest.”

In 1994, Håkan Swahn asked Samuelsson to return to Aquavit to work under the restaurant’s new executive chef, Jan Sendel. Sendel and Samuelsson found they shared much in common and eagerly began to work on their new menu. This was a great honor for Samuelsson, considering the restaurant’s international reputation. In addition to its popularity in the

Sadly, just eight weeks after they began working together, Sendel died unexpectedly. At 24, Marcus became executive chef of Aquavit. He also, soon after that, became the youngest chef ever to receive a three-star restaurant review from The New York Times. In 1999, the James Beard Foundation also honored him as best “Rising Star Chef.” In 2003 they named him "Best Chef: New York City." He started a second New York restaurant, Riingo, serving Japanese-influenced American food, and published his first book in English. Samuelsson is an adjunct professor in meal sciences at Umeå University in Sweden and he has a television show, "Inner Chef." His cooking combines international influences with traditional cuisines from Sweden to Japan and Africa. Samuelsson recently appeared on Iron Chef America, first airing on June 8, 2008, and was defeated by Iron Chef Bobby Flay in battle Corn. Samuelsson is proud of Aquavit’s consecutive four-star ratings in Forbes’ annual “All-Star Eateries” feature. He was individually recognized in Crain’s New York Business’ annual “40 Under 40” at age 29; and was celebrated as one of “The Great Chefs of America” by The Culinary Institute of America.

Most recently, Samuelsson has been recognized by the World Economic Forum as one of the “Global Leaders for Tomorrow” (GLT). The award, given out annually since 1993, recognizes  young innovators from all corners of the world in the arenas of business, government, civil society, the arts and media. Both Samuelsson’s talent in the kitchen as well as his successful business achievements continue to be recognized locally, nationally and globally.

young innovators from all corners of the world in the arenas of business, government, civil society, the arts and media. Both Samuelsson’s talent in the kitchen as well as his successful business achievements continue to be recognized locally, nationally and globally.

Samuelsson’s cuisine continues to win national praise. He has been featured in numerous publications: Gourmet, USA Today, Food & Wine and The New York Times, and Bon Appétit, to name a few and has appeared on ABC’s “Good Morning America,” Martha Stewart Living Television, CNN, The Food Network, The Discovery Channel, UPN’s “The Iron Chef USA,” and several New York television programs. He was the third chef to ever write for The New York Times’ “Chef’s Column,” and is a contributing editor to Savoy magazine.

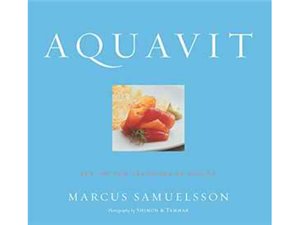

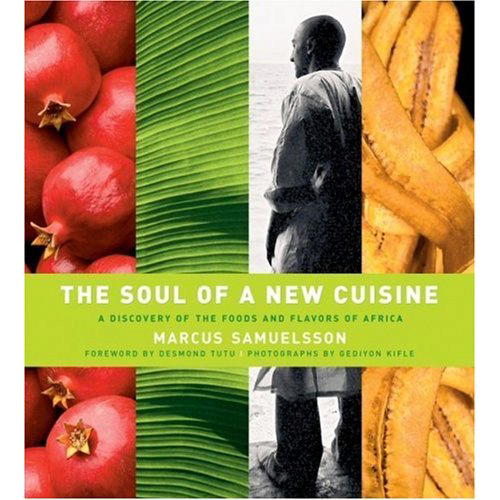

He has written 2 books, Aquavit, which is a mirror of the concept in his Scandanavian resturant, and the more recent book "The Soul of A New Cusine," with its focus on his African roots. Additionally, Aquavit launched a new line of traditional Swedish prepared foods from recipes Samuelsson developed and researched.

On the philanthropic front, Samuelsson furthers his commitment to children by acting as the official spokesperson for a partnership between Dawn Dishwashing Liquid Antibacterial Hand Soap and the U.S. Fund for UNICEF. As an ambassador for the cause, he will help provide support for tuberculosis initiatives in developing countries—an issue close to his heart, and the very disease that robbed him of his birth parents. Most recently, Samuelsson conceived and spearheaded the first annual “Gourmet/UNICEF Trick-or-Treat” program which brought on board restaurants across the country to donate $1.00 per diner to UNICEF on Halloween: helping unite the country’s best restaurants, a global charity, and the highly-respected food magazine.

On the philanthropic front, Samuelsson furthers his commitment to children by acting as the official spokesperson for a partnership between Dawn Dishwashing Liquid Antibacterial Hand Soap and the U.S. Fund for UNICEF. As an ambassador for the cause, he will help provide support for tuberculosis initiatives in developing countries—an issue close to his heart, and the very disease that robbed him of his birth parents. Most recently, Samuelsson conceived and spearheaded the first annual “Gourmet/UNICEF Trick-or-Treat” program which brought on board restaurants across the country to donate $1.00 per diner to UNICEF on Halloween: helping unite the country’s best restaurants, a global charity, and the highly-respected food magazine.

Marcus also dedicates his time and talent to the Careers Through Culinary Arts Program (C-CAP), a non-profit organization that provides inner-city high school students with training, scholarships and jobs in the restaurant and food service  industry. Samuelsson also serves on C-CAP’s advisory board and as the restaurant chairperson for the annual spring benefit.

industry. Samuelsson also serves on C-CAP’s advisory board and as the restaurant chairperson for the annual spring benefit.

Marcus Samuelsson spends his free moments painting, reading cookbooks, visiting museums, and playing soccer. When asked about his goals for Aquavit , Samuelsson says, "I want to ensure that each guest has the ultimate three-star experience, and leaves Aquavit feeling like they’ve taken a little trip to Scandinavia without leaving New York.”

Elaine: Listening to all the experiences you had while on your global travels I understand that you journal. Do you still do that? Marcus: Yes Elaine: Do you refer back to your journals whenever you’re in the creation mode? Marcus: It's different today. I can use my phone to take pictures or just record something, but also when I was traveling, it was very clear as to what I was doing. I was getting my Masters in cooking. I knew I was at that stage and I most likely would not go back there again, so it was very important to retain all the information I could. Mess around with it or whatever I had to do and put a record somewhere that I could take back out. Now-a-days, being in New York, consistently talking to guests, it's different. Now I'm running a business, I'm checking on things, I'm running food. At that time there was no staff to think about. It was just me, a very selfish time. Every individual that starts anything has to have that happen. The pure of me, getting the information. Elaine: As we are talking here, you’ve become reflective and introspective. I'm hearing you talk about who you were and who you have become with regard to food. Marcus: I mean it was also more about being very honest about what you don’t like. We’re in a field where you actually get rewarded for what you don’t like and flipping that into something you do like. Learning about sour and where to stop with it. Or bitter, how long with bitter do I want to go. How much is too sweet. Sitting here, we are three different people and we have three different sets of taste buds. But as a chef, cooking has that. If you work in the post office, those are things you don’t have to develop necessarily. There are probably four or five other fields that you actually get rewarded for your opinion, where your opinion actually matters, not a vague opinion, but your opinion. Your writing about food or chefs for instance. Early on, that was something that I took notes about. What changed was that I graduated from regional cuisine, cuisine that was supposed to be executed in a certain way, where your own opinion didn’t matter, to personal cuisine. Elaine: You’re absolutely right. That was a huge shift in the food industry. Marcus: HUGE shift…and that didn’t happen over night or over a day. There weren’t any hours on the ship to notice a change or anything. I see it in other things, like your iPod. What you download on to your iPod is what you like. Think about the internet. What you search for is what you need, you look at what channels you want, and every individual is doing that. We are becoming more and more individualistic and food now fits into that. Elaine: Right, because food originally is that communal experience. Every culture has that, with every emotional experience that those moments create. I agree with you that in today's society, we have this technological infusion, if you will, that is now individualizing cuisine and I think that is a greater challenge for you as a chef. Marcus: Well, you've got to be relevant to that area your serving, so you have to adapt. Also the internet has many advantages. You can get more information much quicker then you could before. You want to know the difference between red and green curry, click, in like one second you've got it and you have three different options to look at. Lou: (Winks) There’s the concept of our magazine. Marcus: Exactly. Elaine: (Laughs) Yeah.. one click! Talk to us about working in France. Marcus: Working in a four star restaurant, for an old French person, is very much like trying to get into an Ivy League college. You know you can be smart and you can apply, but if there are about 7 colleges, you only need to hear back from one. In France there are about twenty-nine four star restaurants and I must have gotten 29 nos before I got that one yes. For me it was about applying and applying and applying. Eventually, I would get an answer, I would get a yes. For me the best experience is that when you're at a four or three star restaurant every person there, even the guy who sweeps the floor, sweeps with a clear understanding of what this restaurant is about. You know the dish washer washes the dishes with a heightened sense of urgency. The servers running and walking do it just a little bit different. This is all stuff you have been alluding to from my past experiences. Being in that group of a hundred girls and boys that did that everyday shapes you, you know, like playing at Carnegie Hall or something great. You have certain levels to pass for yourself in order for you to say, I can do this. France was my school for that. Elaine: All these little nuances. You became this adventurous, over the top creative individual from your cruise ship experience and now your bringing that into what you call a high end restaurant in Leon. Now here you are in Aquavit. How did this all come about?

Marcus: I did an internship here and I knew I wanted to come back to New York and just connecting dots together like that, wrote a letter to my business partner and he took me. I thought that working here wouldn’t be the biggest challenge if I did it with the same values I had learned from all the experiences I had before. I thought we could get it done. And we did. And we do everyday. I think food in America was already great, with the market already kicking and the fish market already delivering four to five days a week. It wasn’t as extreme as it is now. The fish guys deliver twice a day and the bread guy three times a day. The soul of those farmers in New Jersey, or upstate NY was the same then as it is today. They wanted to have the best delivered to the restaurant, or to the cook. It was a little bit of a different generation, well, let's go back even further. You had young guys who were just starting and now are well established . You had; David Birch, Sherry Palmer, Bobby (Flay) was brand new. These are all guys from here and what I liked about them was that they were not French. Not that I didn’t like the French guys, it was just that , "Oh wow, it's American young chefs coming up." I always thought that interesting. At the same time, Jean George was very young and Eric had just come to town and Daniel. You had a blend of French guys coming here and looking at what American chefs were doing, then American guys going to look at what the Freench guys were doing. That just tells you that this was going to be a good food town. It was an interesting time… Elaine: ....and you were right there. It seems like after your first internship here in New York and I want to make sure I get this right, you said, "What appealed to me most and what made me want to ultimately make this my home was that by being here I had the chance, for the first time in my life, to discover another side of my identity beyond being a Swedish man, where I could also explore my heritage of being an Ethiopian." It seems like from that point on, you developed a long term plan because you knew that you wanted to come back here, tell us about that… Marcus: You know that New York truly has diversity and growing up as a black kid in Sweden was great, but you were always the odd kid out, you always are. Here your not because there are people from all different places in the world. It was just so nice not to have the starting point of "Where are you from? Oh , you speak very nice Swedish." You know those comments are actually very nice comments and their intentions are pure, but it was nice not having to start there. Lou: Basically you were able by being here, to eliminate that first part of the conversation with people, which would have been, 'Oh, how was it being in Sweden?" Instead you have it be simply 'Hi, I’m Marcus...' and start from there. Marcus: Yeah. Like, "How are you and show me what you've got." I think it's very similar for a woman walking into a man’s world. You just don’t want it to be about gender, you want to say, "I’m here and this is what I've got." Lou: Just take it with limited interactions first. Marcus: Exactly, and with New York you always have that, because people here, most of them, are second or third generation. You don’t assume anything. You can’t assume. You just have to start with the utmost respect and then you start to get to know everyone. It’s pretty nice… Elaine: I want to dwell more on the topic of the palette of flavors and that side of you. You've said, "The palette of flavors is essential to a creative chef." In my night time readings, these have become like a bible to me (referring to his 2 cookbooks). They go with us everywhere. The diversity of seasonings that you use and understanding the global experiences you've had, your repertoire is quite extensive. I would like you to share with us, if you would, that creative process as you took a traditional Swedish dish like your foie

Marcus: Well, foie gras is something that as a chef coming up, you work with all the time. It's always the ultimate expensive food. Your truffles, your lobster, your foie gras. I was very clear about, "I didn’t want to serve them that." I wanted to have foie gras, but I didn’t want to have the tureen of foie gras or that sort of or seared piece of foie gras. I started to think, "Well it is not the ingredient that is wrong, it is the texture, it is the presentation." So how can we then shift this from that texture or that presentation? What can we do? I did foie gras pancakes, then I decided that there was too much flour so I took some flour out. Then it was too eggy. You go through this ritual many, many times until you decide, "If I want different texture, then I can mess with the temperature, then you say "Oh I got it!" And that’s how it became ganache with me because, ganache is based on it's hot outside and warm inside and then I get the texture I want. It took a long time. It's very technical and took me quite a long time. Lou: So now you’re in the science of the actual product that you’re working with. Marcus: Yes and that helped me because I’ve done the study of the cooking techniques in France for example. Starting points begin with what you don’t want the customer to experience. Elaine: and working backwards from there, interesting. Lou: Wow that’s very interesting… Marcus: Customers now-a-days, they have experienced everything, they have been everywhere. So you have to show them something different. Elaine: And I know that’s one item on the menu you’ve said you’ll never be able to remove Marcus: No it's there and it’s going to stay there. Lou: Because it’s so popular? Marcus: Well, people ask for it and it's a signature. I think it shows a level of elegance of what you can do. It's also intriguing. Lou: One of our favorite things to do is give a chef back his menu and say, "Here just take us on a flight. Take me on. I can't have walnuts, I don’t eat apples, Now let's go." We’re into that adventurous side of where can you go with this, so when we come across something like your foie gras dish, we say "Wow that’s going to be awesome to try because it does take us outside the box." We love that but a lot of people aren't so adventurous. Marcus: Just like that. But it requires that people are foodies, you know. And those are words that weren’t in the text for food before. You could be a soccer fanatic, you could be a baseball lover and this is something that came around in the '90s, this term (foodies). People have always dined , but now what I found, what was happening in the '90s, is that people were really dining and wanted to know the amount of detail that was taking place in cuisine. Not even in France had that amount of detail going on. . Elaine: I think part of that has to do with the fact that people are not afraid to attempt what you have created in their own homes. They then share that with their families and friends, which then comes full circle. Those people want to come and see you and want to experience the other side of it with you. Marcus: That can happen in a good scenario, but most likely won’t. Because it is very difficult for a home cook. It’s a little bit of the oven and different pots and pans. It's just that some things are meant to be shared and some things are meant to be experienced. There is a difference. Elaine: Hakan stated that "the result of what you do is cuisine that is in motion, looking back and ahead at the same time." To us that is evident in the creation of your dishes, where you seem to be less about technique and more about flavor. You're paying more attention, like you said, to temperatures and textures and bringing contrast to those bright paintings that you create on the plate. When you go into your kit of ingredients, what goes through your mind as you start to create this bright painting for your customers… Marcus: Well your food, ingredients aside, because you look at something and then you decide on what your going to make and you're really going, if you have a pen I can show you. (Marcus then drew a diagram of how he creates a dish) Flavor here, then country, originally you try to recreate a dish from a certain country... Lou and Elaine: that’s culturally… Marcus: ... the cultural experience of that country. For me, fish and seafood right, game meat, pickling and preserving in seasonal. Elaine: You're talking seasonal on all levels, right? Marcus: Yes, these are all things that you need to create food. In other blocks (diagram) you have temperature, texture, and you have other values that you may want to follow. It can also be local, because you want to support certain values, but then today you can be global at the same time. You have to be glocal. This will now drive exactly how a dish is to be served. Lou: Glocal, that’s a great term. Have you patented that yet, we have to attribute it to you, heard it first here. Elaine: and appearance was a big factor… Marcus: Very, very big factor, but today when you create food, flavor is number one. So, if I wanted to do smoked salmon today I say, "Okay I can get wonderful Alaskan salmon" and I smoke it. I use technique but I smoke it much less then I did twenty years ago, because you used to smoke it to preserve it, but today we smoke it because of the flavor. It’s the middle of summer, so I’m serving it with heirloom tomatoes that I’m getting from a guy in New Jersey, so I’m local right. I have all these different fresh heirloom tomatoes and I’m smoking my salmon very light almost like sushi so the texture does not change, the flavor will taste better and then maybe I’m adding some spice from India. All of a sudden then I’m global with the hint of this and aesthetically I’m thinking about the positive and negative space on the plate. That means that my smoked salmon might be perfectly pink inside with red outside, because of the Indian spice and I serve it with local goat cheese, tomatoes from New Jersey and perhaps a little bit of caviar over here on the plate. This is how we create. Thinking of the aesthetic, wrapping it with spice. That’s just one example of a dish, but that’s how everything goes through my mind here… | Lou: I have to tell you we have been talking to a lot of chefs, and I will qualify that you are in the upper rankings of chef’s in the world and you know that, but I have to tell you, the creation process has never been so succintly explained to us......, it mirrors your cuisine here at the restaurant in that the quality of what you present is very, very evident........but it's the simplicity of this plan that creates the complexity of what comes out on the plate. Marcus: You also have to take into consideration the age of some people working in the kitchen, because there is no way a kid of twenty-five or twenty-six from New Jersey, has been to all the places that I have been to. There’s no way! They have the intent and they have the passion and if they work really hard they are going to get there, but I am their voice and their guide to all these experiences and then they will take that and surpass me. That’s progress and you cannot be afraid, so you have to do some of the very basic food that way. The customers sometimes have had much more experience, but customers usually have a little more money and they travel or come from different backgrounds, so they can understand, because they are often professionals in other fields. Lou: Now take that thought for a second. Your diner or your guests' expertise level in terms of their knowledge of what they're eating has gone up dramatically. For example, we are very discerning. We walk in and we’re picking apart this sauce, that preparation. There’s a little too much of this, maybe not enough fennel. We’re that kind of diner. Has that that been a big challenge for you, keeping up with the diners' increasing knowledge of food and cuisine? Marcus: The bar is higher. People expect more, but I don’t see it as a big distraction because you've got to have a comfort level when you work. People feel when your uneasy and people feel when you flow. As a creative individual, you have to go with your gut, with your soul, with your heart and with your mind. A customer can drive what's going to be ordered and what's going to be trendy, but they cannot drive the thought process. So whatever it is, you've got to shoot, you can’t be like, " Oh, I should have shot here." You've just got to shoot. It does sometimes makes a difference. A customer can come in with a very educated opinion and if enough customers come or call you for that, then you might have to go back and rethink something. But you can line up fifteen people and receive fifteen different answers. This is how we see food, my team, my group. Then you can put whatever accents you want to. You can put Japanese food, you can put Swedish food. You can put it next to each other. But this (referring to his hand drawn diagram) is the sifter that all food has to come through, whether chicken or duck or lamb, it doesn’t matter. Lou: Doesn’t matter whatever it’s going to be, excellent. Very intriguing. Elaine: I will tell you Marcus, these cookbooks absolutely fantastic. When I said that I have been reading them like someone reads a novel, it's an understatement. Marcus: (Winks) I'm working on the next one now… Elaine: I'd like to talk to you about "The Soul of a New Cuisine." Because this has passion, I mean real passion. I was just overcome with the essence of you ,while I was reading it. Give us your first impression. You put your heart and soul in here and it’s evident. When it was done and it came out and you looked at it, what did you feel? Not just the "I’m done, I have success" but this is you…

Marcus: Well I didn’t feel that it was done. I felt,"Now the journey starts." On with several different trips. It starts when you thought about it, when you cooked the dishes and tried it out, then went and took photos after writing and cooking all the dishes and then when it is done, you think, "Now I am going to be the ambassador of this book." You've got to go out there and do promotions and in our world, promotions means cooking. It was great going into a room of fifty excited people and cook the dishes and they became even more excited when they tried it. When you’re done and they go and tell theit friends, there’s fifty more people. That level wasn’t really the heavy lifting for, that aspect of the whole thing was fun. Going to Wichita, going to Austin, where people had never been to Africa, maybe didn’t even know someone of an African descent. You know, there’s the east and west coast, like San Francisco & New York. People are very liberal, people have seen and experienced and know what’s up. And those people are easy. It's much harder with people who have never experienced it, so I never really felt it was done. It was the beginning of the next leg, the connecting of the dots was what you guys did. It only becomes connecting when you do what you guys did. And that is cooking it. Taking it to a different experience and getting a reward from completely different people that you know might not know about it. That’s the whole outlook and that’s what shapes how you experience with confidence. We’ve done it with Italian food, so much so, we all have our own version of Italian food. We started with pesto, with simple things. But now every one knows that they can do pesto with broccoli, you can do pesto with cauliflower, you know? There are a million things you can get out of it. We didn’t have that dial-up, that connection, when it came to Africa and so the intent of the book was to create that dial-up and change how we view Africa. It's not all AIDS, war and famine. There are a lot of positive stories too. We have a deep culture. Elaine: I loved how you talked about going to the spice farm and how you were being tested and you shared with us how you had difficulty when you first made injera. Lou: They were awesome… Elaine: The first two were thick like pancakes… Lou: and I ate those too… Marcus: Good! (laughs) Elaine: I did finally get them to where it was like what you were talking about. Now there’s a restaurant in New Jersey that introduced us to injera bread and I was looking for you to talk about the mesob table and the whole experience. When I saw the injera in there, I was like, "This is what I’m talking about, this is the bread that goes with that!" But the fact that you bring me a photo journey along with the culinary journey…

Marcus: I had to. I didn’t want the experience that is chopped down into a pocket book. Just like an Italian food inspires people to go to Italy, this book should inspire you to, one day to say, " I want to go, one day I will go to that Tunisian restaurant that I always peeked in but never go to." It should intrigue that curious individual to be like, "You know what? I have been to five French restaurants... let me try this one instead." Elaine: It's as if you have become an ambassador to Africa, you really have… Marcus: Absolutely, but chefs always have been, you know. French food became a big part of the American scene when the French chefs came over and that intrigued a lot of people to go to France. Italian chefs have done that forever so I think that food allows you to become an ambassador if you do it right. Because it's not politics, it's not money, it’s not religion… Lou: It's universal… Marcus: Yes, universal! Where everyone can say, "Hey let’s try this."

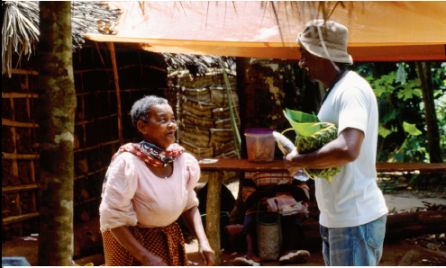

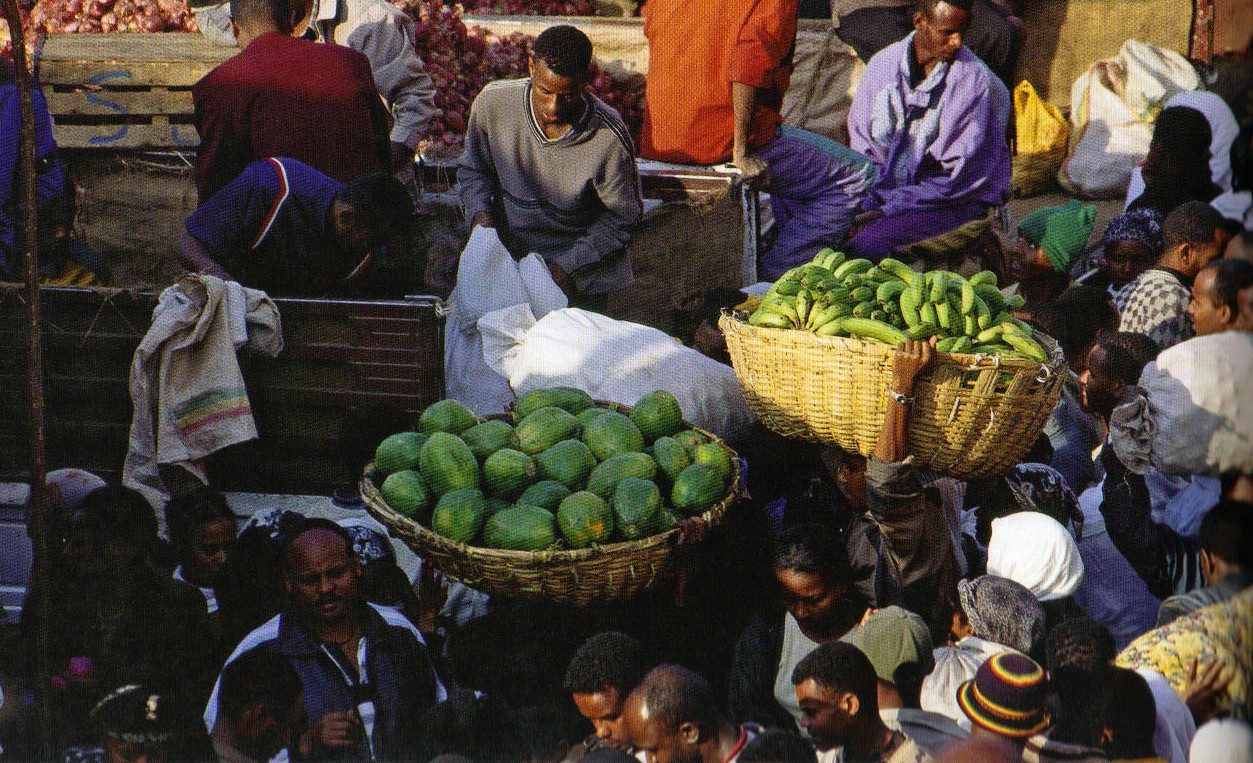

Lou: Go back for me in your mind. you're in the Bahama spice market, or in the co-op. Bring me back there. What's going on there? How is this impacting you emotionally? Marcus: I think that being at the spice market for example, for me it was understanding, like wow, it's actually a tree somewhere, it’s a plant somewhere, it’s a live product. Because spice always implies that it is dried and put together. There you realize oh, well, cloves grow like this. Or the nutmeg comes from here. For me it really makes the dots connect. Injera is something I have eaten so much and taken for granted. It started with a woman making it for us. Pounding it with a stone in order to get the tiny seed, then sifting it. It started with that. Just seeing the women do that was like "Oh my god, that’s a lot of labor. I have worked with labor food my whole life, but with spice it’s a different kind of labor, because it was very direct, it wasn’t a big mill sifting it, it was a big stone and chhh like that… Lou: It’s also a window into who these people are. So on that level it's not just oh I learned about the food, about the spice, it’s the process of that. What I’m hearing from you, you learned about who these people are and how they conducted… Marcus: but it's also how it takes you back fifty or sixty years. Exactly how it went on in this country, all our food was cultivated like that at one point. All our food was organic, and then all this other stuff came in between. So for me just seeing that… Elaine: I think it brings you to a greater level of appreciation when you go to get that off your shelf or out of your refrigerator. Because of your experience, sounds will come to you, smells will come to you. You get transported and I was reading this. I have a passion for food and when I get an opportunity to meet somebody like you, who's drifted away to explore the barest part of it all and then has rebuilt from that viewpoint, it affords me, as an individual who may not get to Africa next year, a glimpse into that world. It gives me the drive to go and experience it for myself. Marcus: But I think you already did it…because you went to that place in New Jersey. Like you, my whole idea with this was, Africa doesn’t have to be this kum-ba-ya experience and you put on… much laughter.... Marcus: ....it can also be, like the fact that you guys already did it with your shrimp, with you trying that place and look now what your thoughts are. Exactly that, curious people will always find out, they will always find out… Elaine: It’s what you make it. The depth of your passion in creating new cuisine is incredible. You afford readers and aspiring cooks the opportunity to experience that through recipes and through photos. I'd like you to catapult yourself back into those markets and help us understand those sounds and smells and the impact that they had on you at that moment. In what I call that 'pinch yourself moments'

Marcus: Well all of these moments. I mean it's, in Africa, ......the process. It's twenty-four hours. Which is the biggest difference from here. Here we sometimes take pride in not eating for the day or 'Oh, I didn’t eat too much today.' In Africa it might be a six year old kid who has to walk seven miles for water and just so somebody can have it. So you know, it starts with that. Someone might be walking with twenty-five onions so they can sell it tomorrow. All of those experiences put you there. It's just a different life all together, but it still has the same highs and lows. People are happy, they laugh, people get upset when they are not treated fair, and people want to have a bargain when they go to the food market.

When people buy things, they pick it up, smell it put it down, and maybe go back to the first one to buy it. The core of it is still the same, but how we got there is a little bit different. You got the stuff on your back, it’s different. But to me the celebrations become harder there. You love harder and you cry harder. That’s why I think the weddings over there are celebrated with five to six hundred people and funerals are celebrated. It's different from here, but they still have food as a part of all this. I think that the emotions are different and it comes out in the food. Spices are there because they preserve the food also, it's very hard to explain and I think when you're fortunate to have a dual culture you can easily adapt to either one and appreciate both, and you see that in America. It's like someone who is from Napoli, when they are here they are fine, and once you go back it's like clockwork there as well. So for me when this happens, when I am there in the market, it feels like this should be happening this way. Put it here it would be awkward. When I am in Europe, I don’t feel the difference. Because Sweden could be a state in America, like Connecticut, like Vermont, very similar, you’re trading middle class for another middle class. But when you’re going from Sweden to New York to Senegal...... it is a difference. It’s a big difference. Lou: You don’t necessarily, from what I’m hearing, over analyze it, but it has shaped you. You like being in the moment and not over analyzing because you’re just experiencing it and what comes from it later on is how it affected you. Marcus: Yes, and you see how the situation when you're not there, you can say, " Oh I have done this before, I have seen this before." Now when I went to the food market in Acapulco, I had no idea it would be similar to the food market in Africa. Elaine: I think by having that experience, you can really get to know who the people are. Well, we know that you are very busy, so we'd like to wrap this up here and ask you if we may sit to do part 2 of this at some point down the road, say when the new cookbook comes out? Marcus: Sure I'd like that. You did say you are eating here tonight right? Lou & Elaine: Yes we are. What do you recommend? Marcus: Do the Chef's Tasting. We'll do both sides for you and you can get a taste of eveything that the resaurant has to offer. Elaine: We'd like to thank you so much for spending some time with us today. Marcus: No problem. It's been my pleasure, Thank you. |

At this point ,we then posed for pictures and scheduled part 2 of this interview with Marcus for when his new book comes out. The evening's meal was spectacular and Marcus and Chef Johan Svensson gave us not only a tasting from the main dining room, but also served us a few courses from the more casual Cafe out front. They wowed us with a 3 hour tasting not soon to be forgotten. You can read all about our evening at Aquavit in

gras and rebuilt it into "foie gras ganache."

gras and rebuilt it into "foie gras ganache."

I will let you know it took me several times to get it right. It is very hard to do, and like you said, I don’t have that beautiful big work space that they had…

I will let you know it took me several times to get it right. It is very hard to do, and like you said, I don’t have that beautiful big work space that they had…